Since 1 January 2019, fishermen in the EU have been required to land all the fish they catch–including the unwanted fish which previously would have been returned to the sea. But how is it possible to check that all the fish which are caught are landed? And how is it possible to find out which fish were previously treated as discards but which are now being landed?

These are some of the issues which the international research project ‘DiscardLess’ has been studying.

“With the landing obligation, much of the control requirement has been moved out to sea, because you need to know if fish are being discarded. And only very few control mechanisms can check this. At least, if with a high degree of coverage is wanted. Observers on board can check what is going on, patrol vessels can too if they are present, and finally video cameras can verify what is happening. However, by only checking landings, it is not possible to know whether fish are being discarded,” says PhD student Kristian Schreiber Plet-Hansen from DTU Aqua. As part of the DiscardLess project, he has studied video monitoring as a possible control measure.

Video camera footage for registration of species and size

By installing video cameras on the fishing vessels, trained video auditors can quickly register how many fish are being discarded as well as the species and their estimated size. Since 1 January 2019, it has been against the rules for fishermen to discard several fish species, but the data is also important when assessing stocks to determine the future quota levels.

Results from a study where a number of fishing vessels voluntarily had video monitoring installed suggest that on-board cameras may be effective. For example in the case of cod, which fishermen previously had to discard if they had used up their cod quota.

“In relation to the landing sizes for cod, the landing composition changed for some–but not all – participating vessels. For some fishermen it undoubtedly had an impact. At the trip where they started to have video cameras on board, small cod suddenly showed up in the landings, which had not been the case before. This is no proof, but it is an indication that some fishermen changed their behaviour after being managed with catch quota and having cameras on board for verification,” he says.

Video monitoring unable to determine age and gender

However, video monitoring cannot completely replace observers and landings control:

“You can see a lot with video monitoring, but there are lots of details that you cannot determine. Age and gender identification is not possible, and species identification can be problematic, especially for certain species of flatfish. And to assess stocks, it is important to know the species, age and gender,” says Kristian Schreiber Plet-Hansen.

Insufficient quota for a species is one of the reasons why fishermen discard fish. Another reason may be that the value of the fish too low, because the species does not fetch as high a price as other species, or because they are too small.

Discards can also be used in products

Even if the catch is of such a low value to the fishermen that it would previously have been discarded, discards can potentially be used for many things. The DiscardLess project has published a product catalogue with a range of products where discard fish and shellfish can be used. For example, all species can be used to produce biogas, compost fertilizer, gelatine and fish meal and fish oil, which is used for animal feed.

These products do not require the fish to be stored in crates, and sorted according to species. To save storage, discards are often mixed together in tanks or block frozen on board the vessels. However, this makes it difficult to see the species composition of the discards being landed.

DNA analyses can reveal species in fish mash

The results of another DiscardLess study from DTU Aqua show that DNA analyses may well be useful.

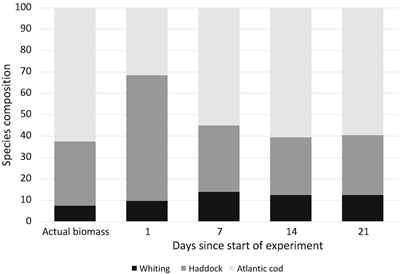

The researchers made fish silage with catfish and three fish from the cod family: cod, haddock and whiting. They then examined whether they could retrieve DNA from the four species of fish–and whether there was a correlation between the quantity of each species in the silage and the amount of DNA. Silage is a kind of fish mash, where the fish are treated with acid so that the enzymes in the fish dissolve the tissue to produce a liquid. Silage is easy to store, even at room temperature, and the product can be used for, among other things, animal feed and biogas, but it is impossible to see from the silage which fish it contains and in what quantity. Samples were taken every day for 21 days, and the DNA analyses gave an indication:

“There is a basic idea that if you have an individual in silage, it releases a quantity of DNA. If you have two individuals of the same kind and size, then they should release twice as much. And this is certainly the case for fish from the cod family. On the other hand, the catfish released a disproportionate amount of DNA, so if you have species which are not that closely related, it is necessary to calibrate input from the individual species to estimate the proportions exactly,” says Brian Klitgaard Hansen, DTU Aqua, who is behind the study.

In the study, there were three to four times as much DNA from the catfish as from the cod species in relation to the actual weight of the fish that were used to make the silage. This may be because the catfish has more active tissues, such as fins and thick skin, which contain more DNA than, for example, muscle. But when the researchers removed the catfish DNA from the calculation, the amounts of DNA from cod, haddock and whiting corresponded quite accurately to the actual biomass of each of the three fish.

DNA tests can determine quantities and species precisely for cod fish

There is still some way to go from these results to a rapid test which enables a harbour inspector to determine species and biomass with any degree of accuracy. However, intense efforts are being made within DNA research and the development of handheld tools. But there are still a number of unanswered questions.

“Our method can show which species are present and provide a strong indication of the relative make-up of cod fish. We have conducted tests with four different species of fish, but it is important to obtain information about the link between weight and DNA content for all key species in the fishery. It will also be interesting to find out why there is a difference in the DNA concentration from the catfish. Is it because there are, generally speaking, differences in DNA concentrations in different tissue types, or are there other reasons? There are still unknowns in the equation, but what we have tested in working with DiscardLess is beginning to open up what was previously something of a ‘black box’,” says Brian Klitgaard Hansen.

DiscardLess is funded by Horizon 2020 EU framework programme for research and innovation (H2020 GA 633680).

Read more at

Discardless.eu